Baseball Is The Language Of Fathers

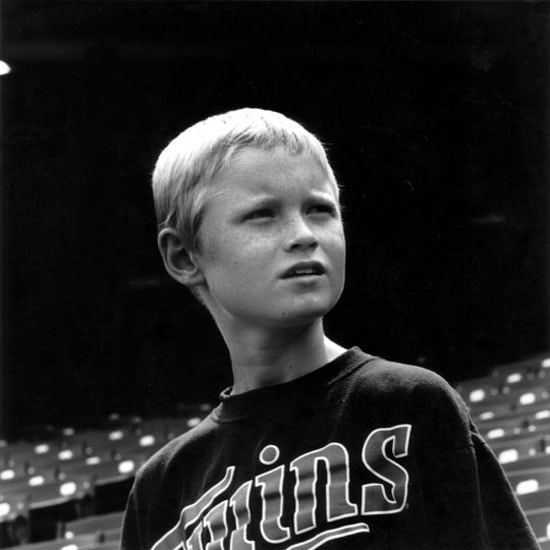

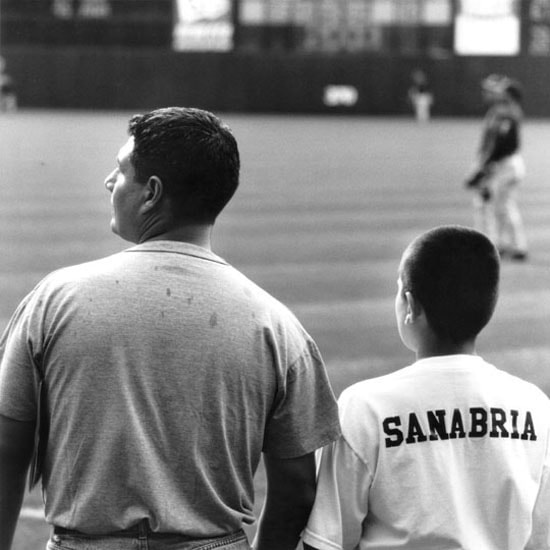

My father used to take me to the minor league games, the Pompano Beach Mets and the Ft. Lauderdale Yankees. In all truth I cannot tell you if we went only once or thirty times. I am intoxicated by this memory.

My mother hated baseball. The Dodgers left Brooklyn that Brooklyn girl told me, but I’m pretty sure that wasn’t it.

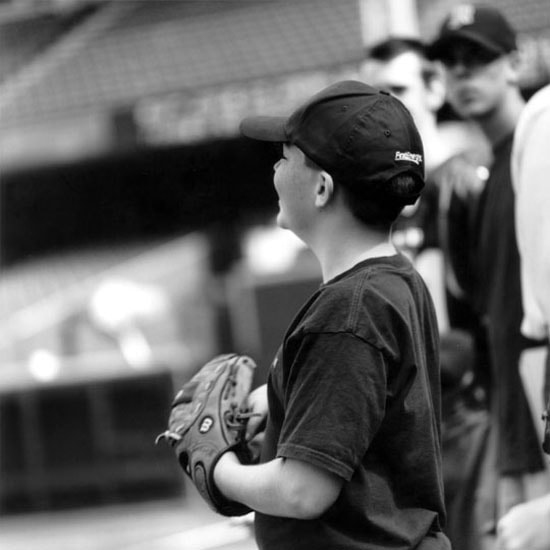

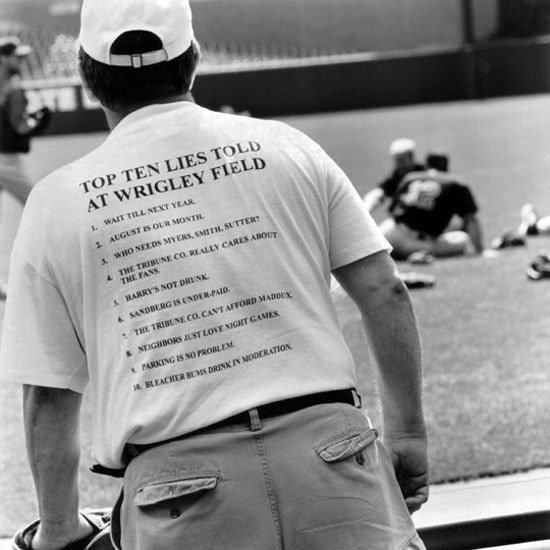

I was born left-handed, but my father made me change. He didn’t want me to eat like someone from the old country. Perhaps baseball for him was the language of a new country, an alignment with something so fresh, and so green.

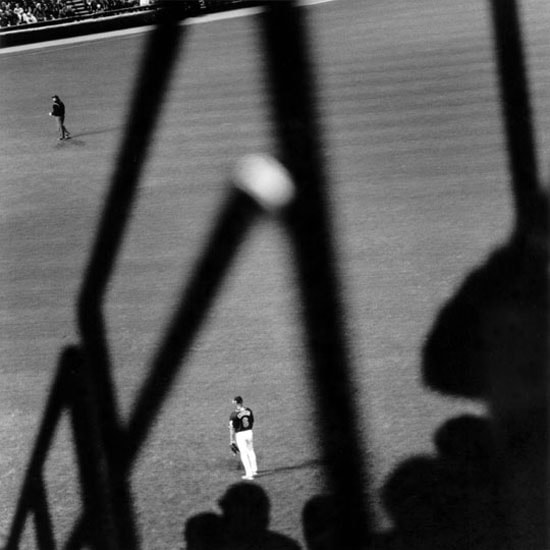

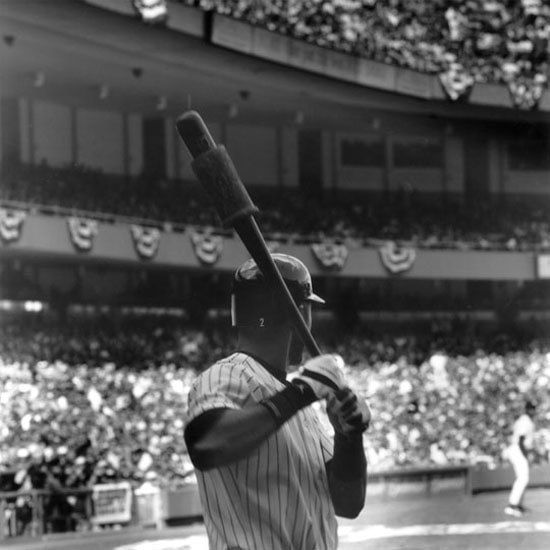

For me: So green. I could tell you how I revel in the aesthetic, the symmetry or rather an organic reflection on the notion of it. I could tell you how it appeals to my sense of justice, law and enforcement, the same opportunity, exactly, for everyone.

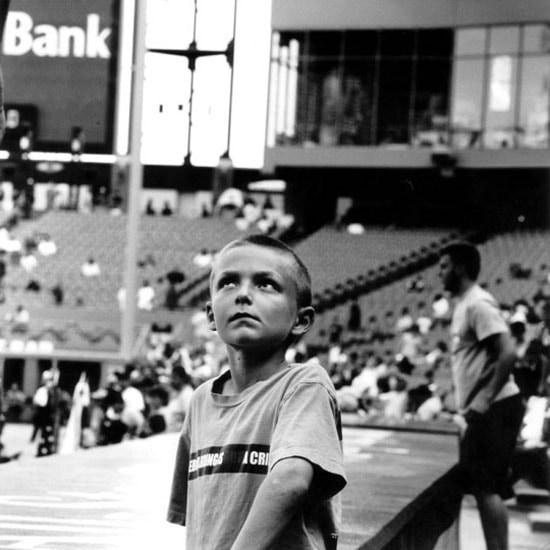

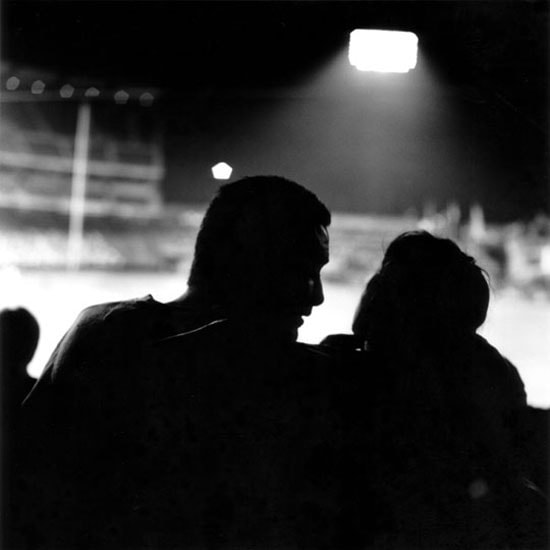

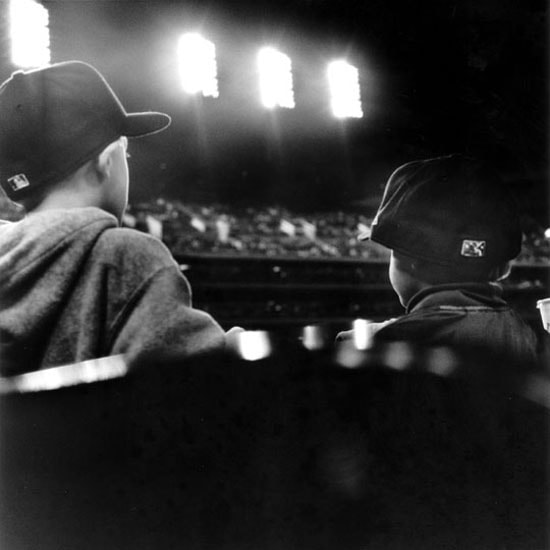

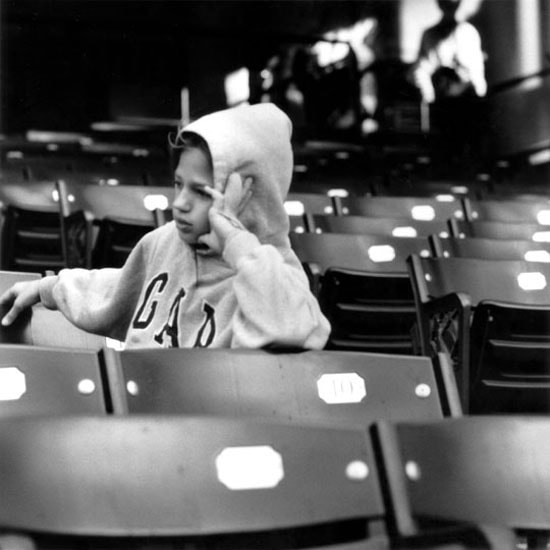

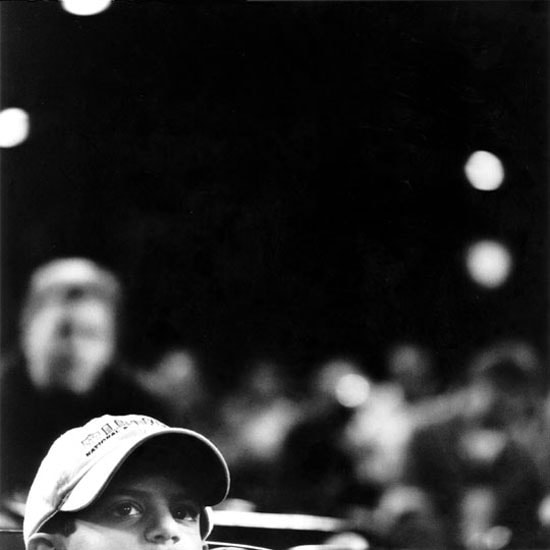

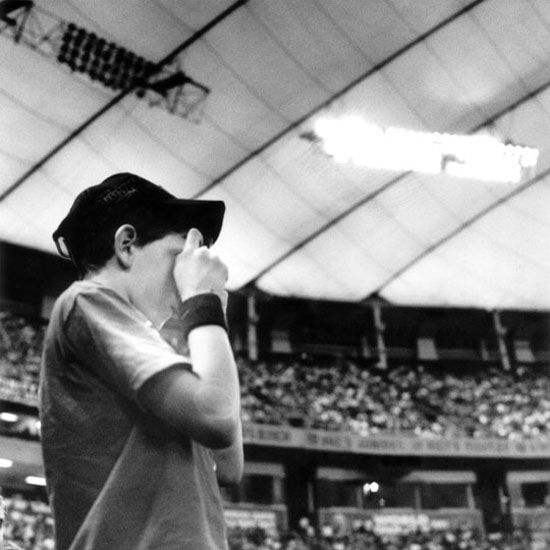

I remember how the bleachers felt, smoother in Lauderdale. I remember how the lights at night made me feel lucid, like every detail could come in. I remember sitting beside my father, proud of that, even then I knew it meant something.

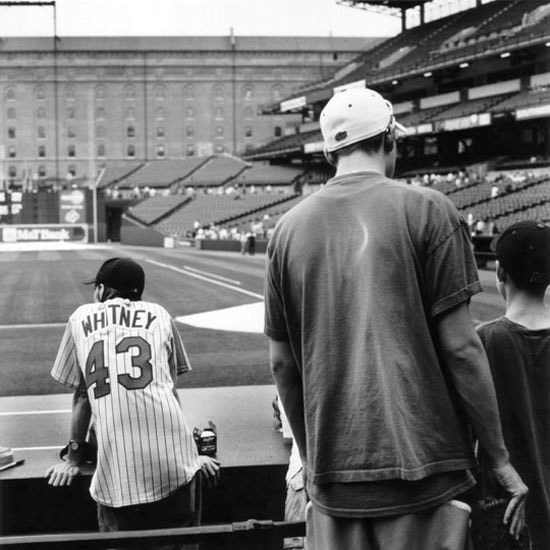

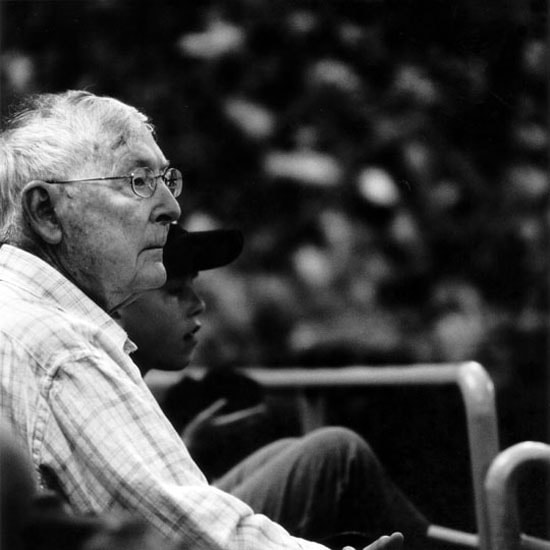

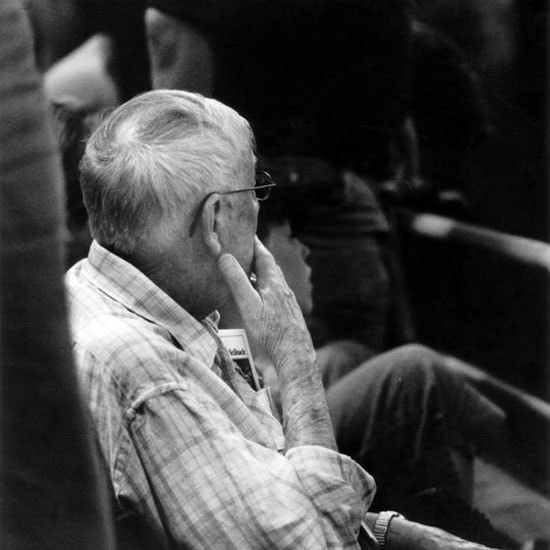

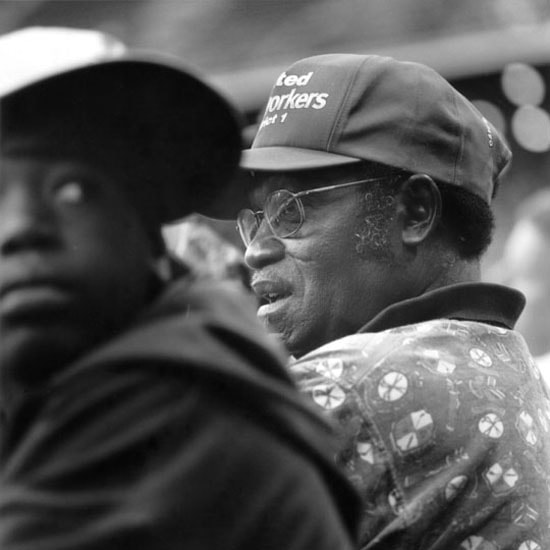

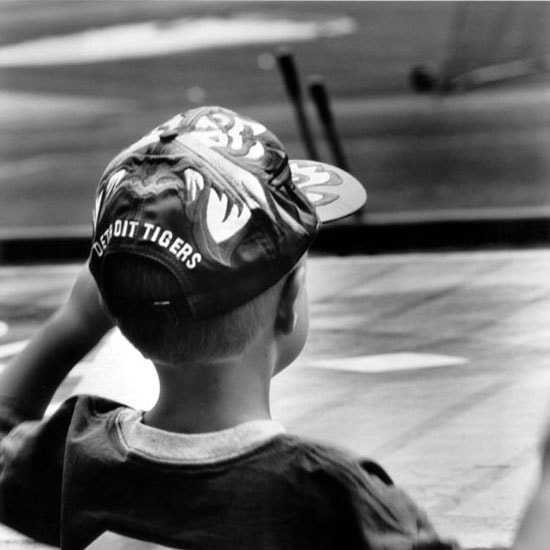

Mostly I feel compelled to tell you with some sense of irony that my father passed to me Baseball like a language from the old country. His passion for it was a door to his soul; his bestowing it on me a key to it. We shared this throughout our lives, throughout the time of his and mine. It was always common ground and safe harbor, a place to rest our interaction should it feel otherwise stormy.

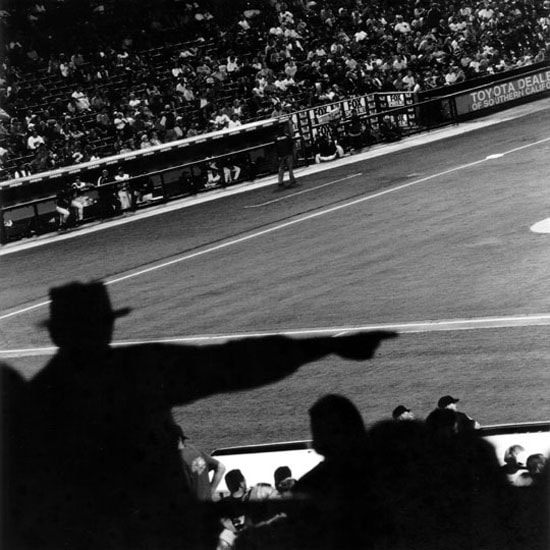

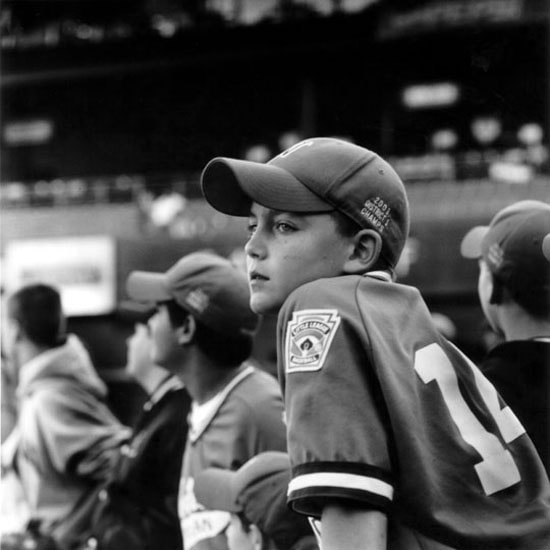

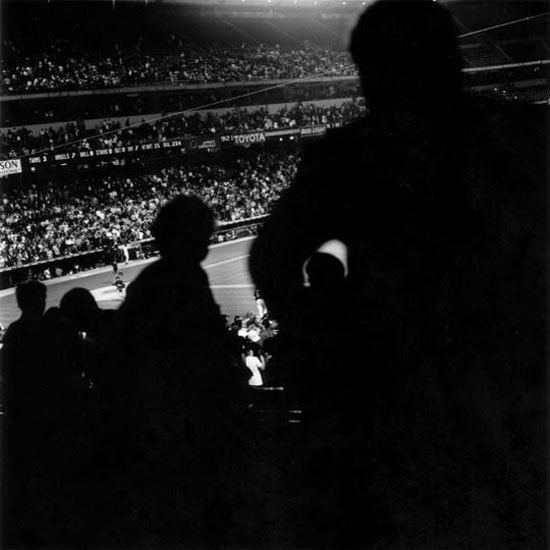

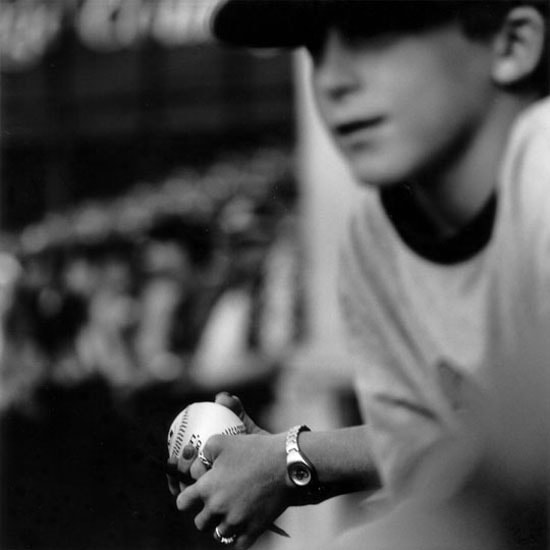

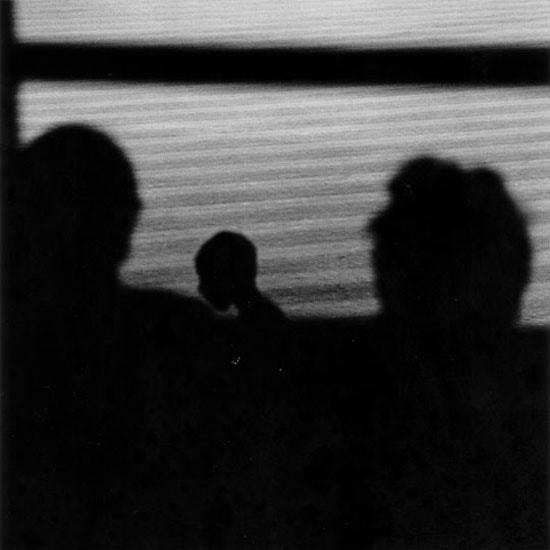

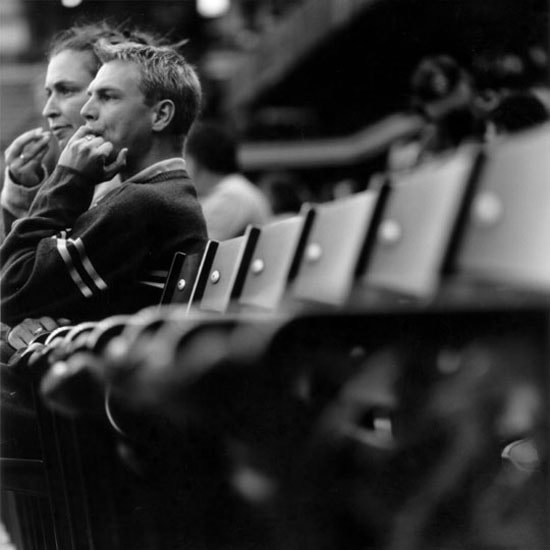

And like a language I speak it with others who do or wish to; it is a bond with a stranger, brief yes yet in context significant. We all feel our fathers there, our children, memories of those we’ve never met or even seen, the great ones, and those we think only we might remember.

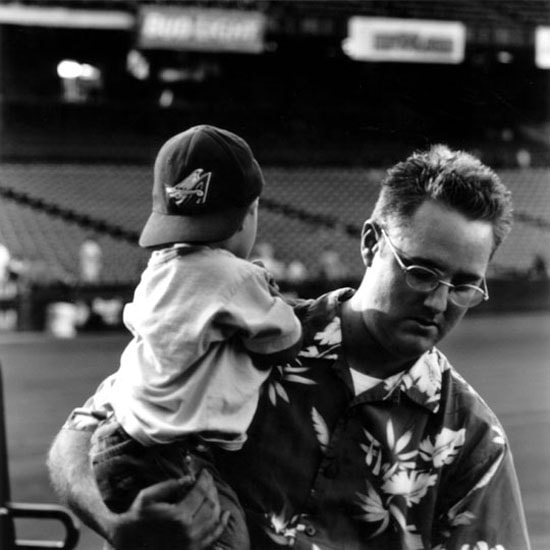

I watch this ritual pass on continually, like genes, like an accent. Grand Father Child Mother Friend: I have in fact hugged strangers. Me there with my own father, now dead. I feel him. He whispers, “Did you see the break on that curve? The runner, he’s going.”

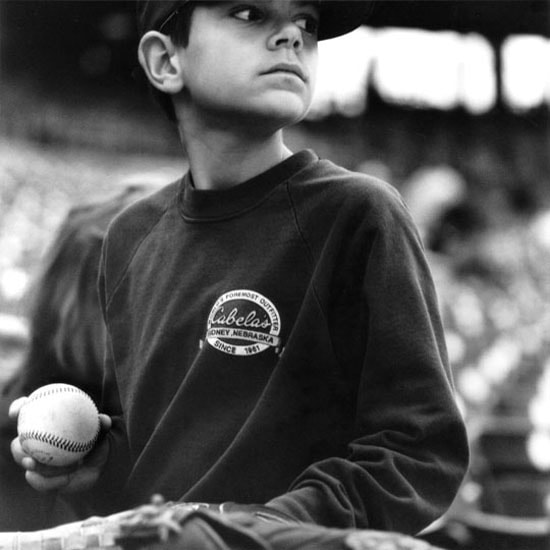

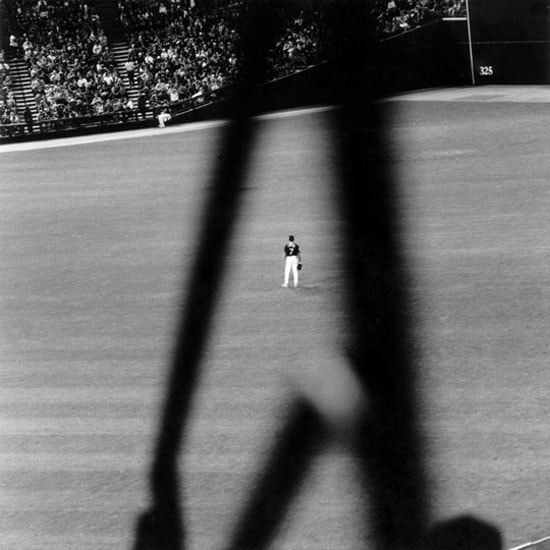

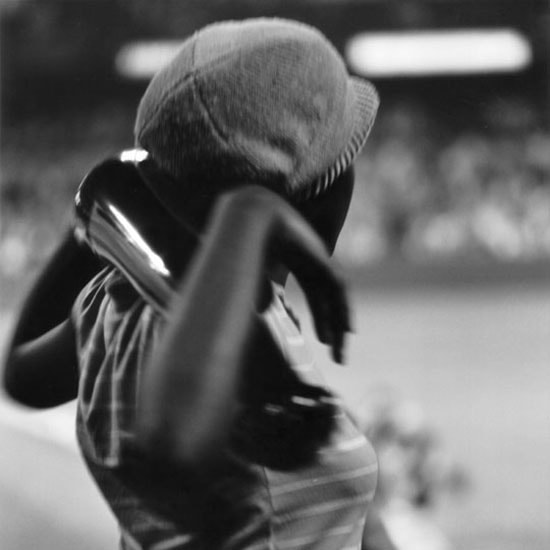

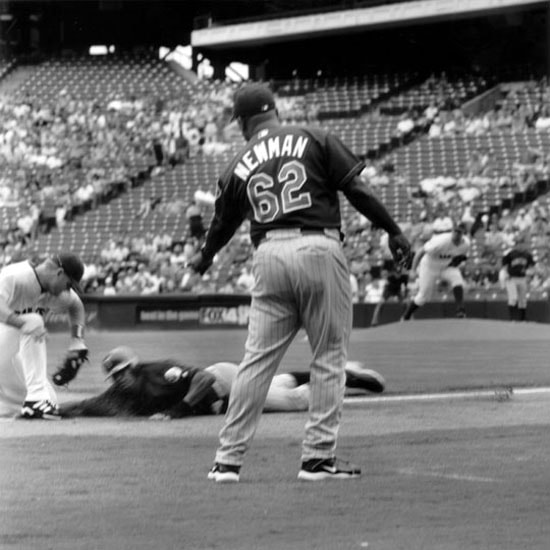

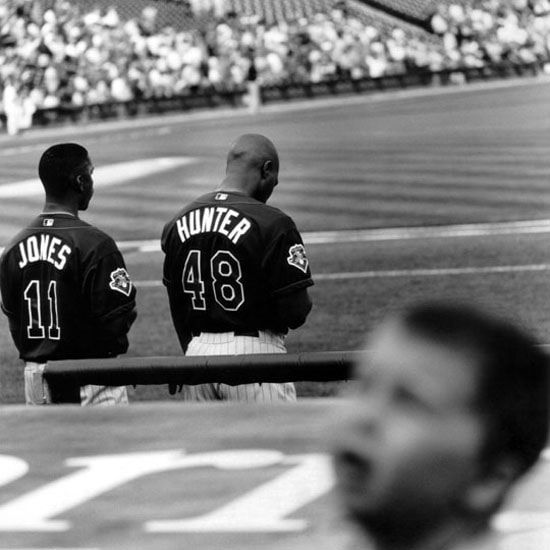

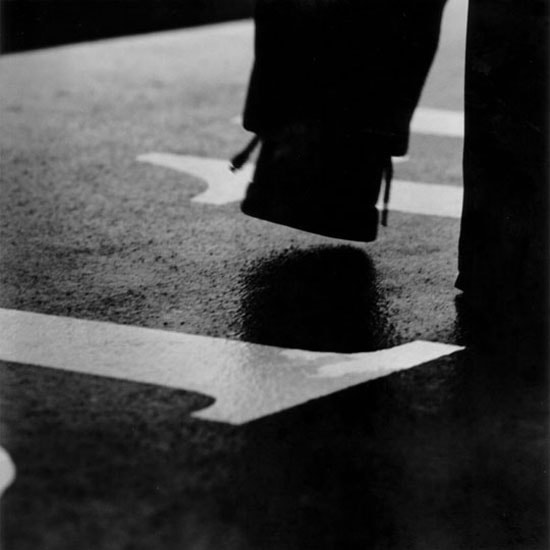

From the stands there in Pompano I have a vision of this player diving for the ball. It is a memory more crisp than that of any of my own birthdays. My father said, “He’s going to make it.”

My mother hated baseball. The Dodgers left Brooklyn that Brooklyn girl told me, but I’m pretty sure that wasn’t it.

I was born left-handed, but my father made me change. He didn’t want me to eat like someone from the old country. Perhaps baseball for him was the language of a new country, an alignment with something so fresh, and so green.

For me: So green. I could tell you how I revel in the aesthetic, the symmetry or rather an organic reflection on the notion of it. I could tell you how it appeals to my sense of justice, law and enforcement, the same opportunity, exactly, for everyone.

I remember how the bleachers felt, smoother in Lauderdale. I remember how the lights at night made me feel lucid, like every detail could come in. I remember sitting beside my father, proud of that, even then I knew it meant something.

Mostly I feel compelled to tell you with some sense of irony that my father passed to me Baseball like a language from the old country. His passion for it was a door to his soul; his bestowing it on me a key to it. We shared this throughout our lives, throughout the time of his and mine. It was always common ground and safe harbor, a place to rest our interaction should it feel otherwise stormy.

And like a language I speak it with others who do or wish to; it is a bond with a stranger, brief yes yet in context significant. We all feel our fathers there, our children, memories of those we’ve never met or even seen, the great ones, and those we think only we might remember.

I watch this ritual pass on continually, like genes, like an accent. Grand Father Child Mother Friend: I have in fact hugged strangers. Me there with my own father, now dead. I feel him. He whispers, “Did you see the break on that curve? The runner, he’s going.”

From the stands there in Pompano I have a vision of this player diving for the ball. It is a memory more crisp than that of any of my own birthdays. My father said, “He’s going to make it.”