County, State

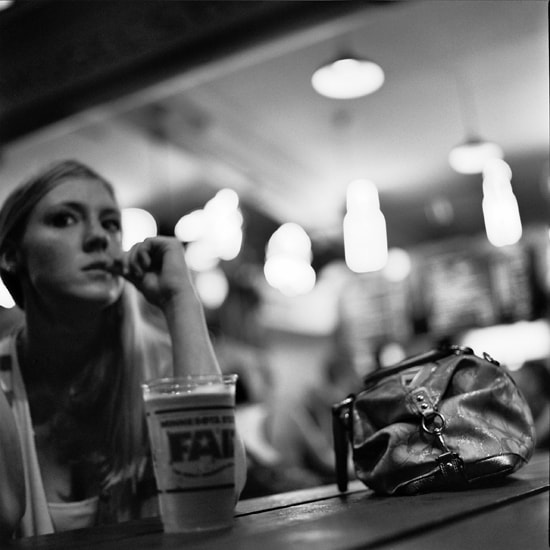

Do we choose our memories? Do we choose the way we remember them?

You could see it coming before it happened, the accident. The horse huge and foaming, the handler anxious. The horse with its neck arched, nostrils red. It lifted its feet so high, it was easy to imagine being crushed underneath them. So when the handler lost control at the entrance to the barn, and when you heard the shouts from inside, that’s what you pictured.

The loudspeaker over the grounds called for the trampled man’s family, and told them they should hurry. Most people probably didn’t hear or didn’t know, but those of us near the accident hovered around it. A girl came by crying, a granddaughter. She was too scared, stayed outside like we did. The ambulance came, stayed awhile, left without its lights on.

Then it was gone. The crowd broke apart. I meant to stay sad but had demolition derby tickets. We had french fries before we went in. I could smell them as we had stood outside the barn. Even then.

Last year there was a stabbing. That’s what people said. We saw the yellow tape and the street by the east entrance was shut down. We didn’t see what happened. No one seemed to. Not even the stoic cop assigned to guard the line. You can ask him questions, but he’ll act like you’re not even there. He could convince you you’re invisible.

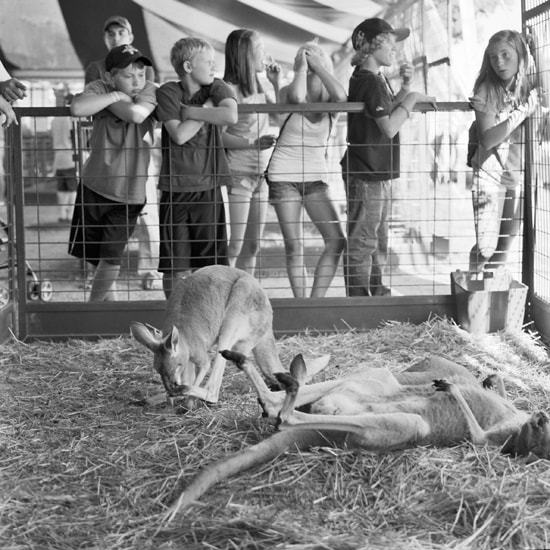

Then we went to see the animals. In the poultry barn a boy held a duck. He didn’t hold it like stock. He held it like he loved it. It was calm in his arms. He let me put my finger in its breast. I hadn’t known until that moment its flesh was so far away, so far beneath the feathers. He had me run my hand across its beak. I hadn’t known it would be so warm.

Do we choose our memories? Do we choose the way we remember them?

I’ve never had a bad day at the fair.

You could see it coming before it happened, the accident. The horse huge and foaming, the handler anxious. The horse with its neck arched, nostrils red. It lifted its feet so high, it was easy to imagine being crushed underneath them. So when the handler lost control at the entrance to the barn, and when you heard the shouts from inside, that’s what you pictured.

The loudspeaker over the grounds called for the trampled man’s family, and told them they should hurry. Most people probably didn’t hear or didn’t know, but those of us near the accident hovered around it. A girl came by crying, a granddaughter. She was too scared, stayed outside like we did. The ambulance came, stayed awhile, left without its lights on.

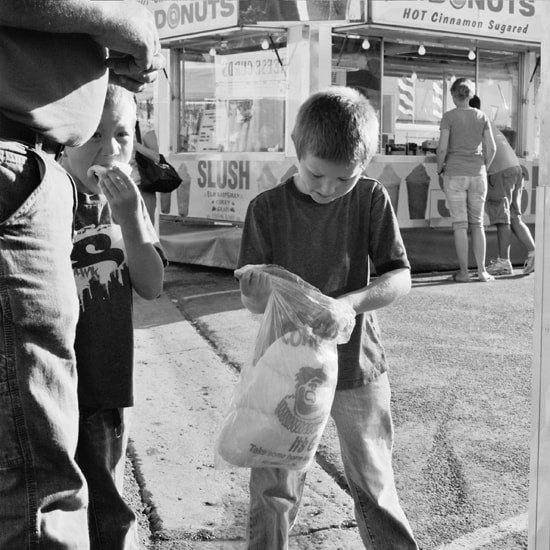

Then it was gone. The crowd broke apart. I meant to stay sad but had demolition derby tickets. We had french fries before we went in. I could smell them as we had stood outside the barn. Even then.

Last year there was a stabbing. That’s what people said. We saw the yellow tape and the street by the east entrance was shut down. We didn’t see what happened. No one seemed to. Not even the stoic cop assigned to guard the line. You can ask him questions, but he’ll act like you’re not even there. He could convince you you’re invisible.

Then we went to see the animals. In the poultry barn a boy held a duck. He didn’t hold it like stock. He held it like he loved it. It was calm in his arms. He let me put my finger in its breast. I hadn’t known until that moment its flesh was so far away, so far beneath the feathers. He had me run my hand across its beak. I hadn’t known it would be so warm.

Do we choose our memories? Do we choose the way we remember them?

I’ve never had a bad day at the fair.