Greater Than

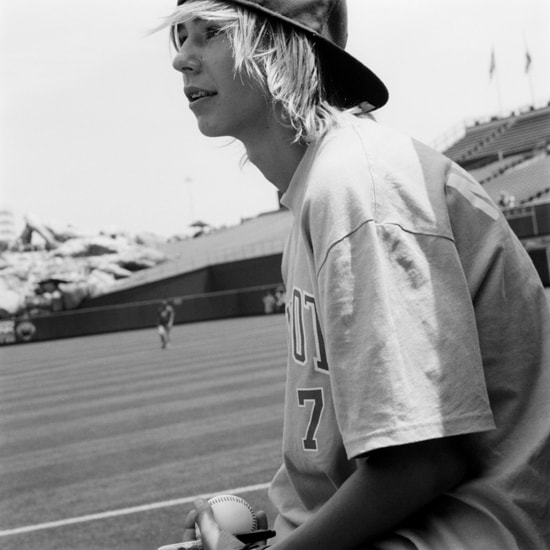

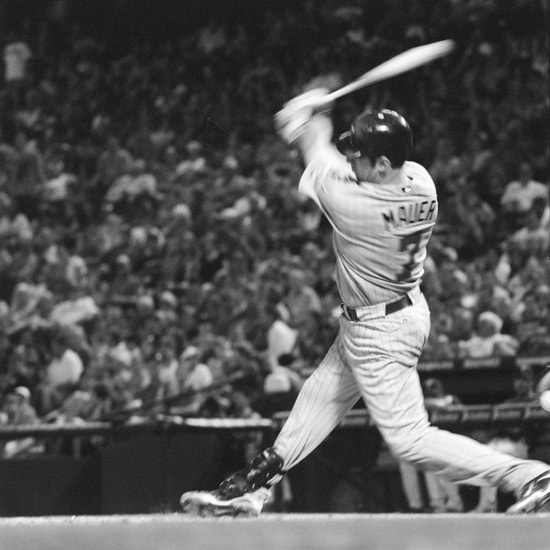

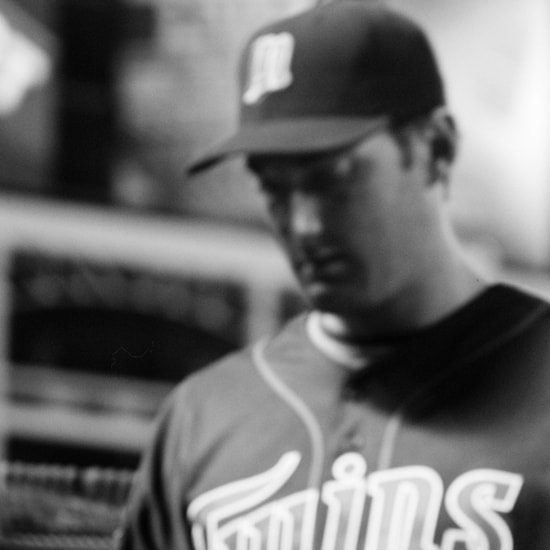

Orlando Cabrera is still a favorite in Chicago even though he didn’t play there long. Fans at the park early for batting practice shout, “O.C.!” the way you’d call to a friend you spotted in a crowd. Cabrera is always busy on the field. He doesn’t tip his hat or even look up into the stands but that’s okay because he’s the kind of guy you know is alright.

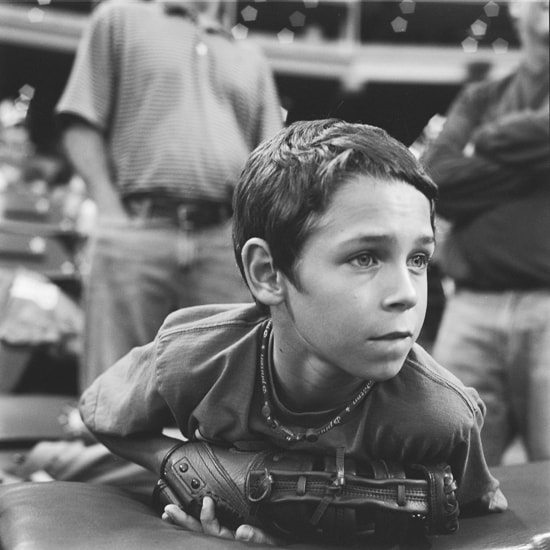

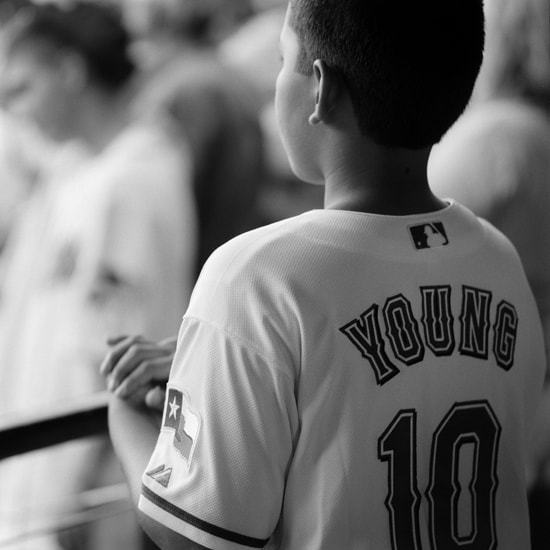

I was in the camera well next to the visitors’ dugout and there were people in the stands calling to me like they always do, asking for a ball. I try generally in this situation not to look up but someone tapped me on the shoulder, a woman about my age and she said, “It would be nice if we could get that boy a ball.” And she pointed, or rather gestured with her chin, not to a boy but a man, a retarded man. He was about the same age as the woman and me. And he really wanted a ball. He was looking, reaching, calling out even though the time for balls and autographs had passed awhile ago. The game’s about to start.

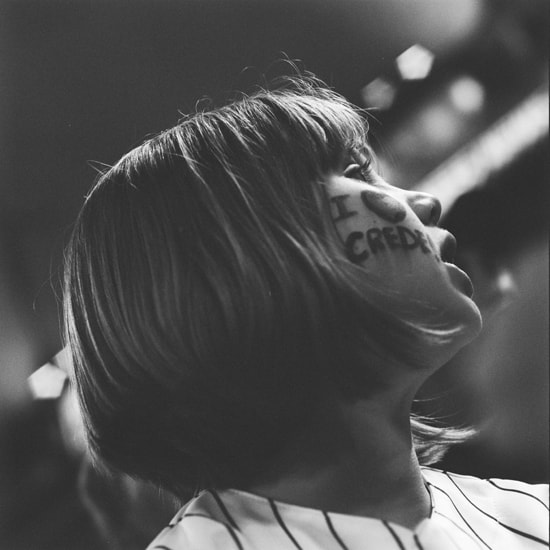

Others join the woman too, asking if I could get the “kid” a ball. I said, “I wish I could,” and my heart is breaking a little bit because the poor timing of the retarded man’s request makes it seem especially innocent. I frown, look around, maybe pout a little so people know I mean it: “I wish I could.” But I can’t. There are rules against credentialed press – like me – asking for player autographs, but there are unspoken rules too. You don’t speak or interact with them on the field, you don’t even say hello. And you certainly don’t ask for baseballs.

Plus, the game’s about to start. The anthem is over. A couple of infielders are playing catch right in front of the dugout just before the game starts. Any second they’ll turn and take that ball into the dugout with them. They’re all business right now. And the man, despite his shouts, is probably a little too far down the line to be noticed anyway.

The head groundskeeper in Chicago looks like an actor and rarely speaks. Mostly he watches. He watches the field like everyone else watches the game. He also watches clouds.

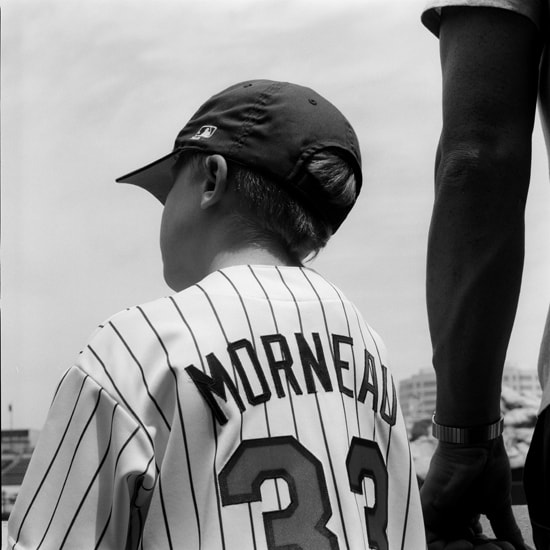

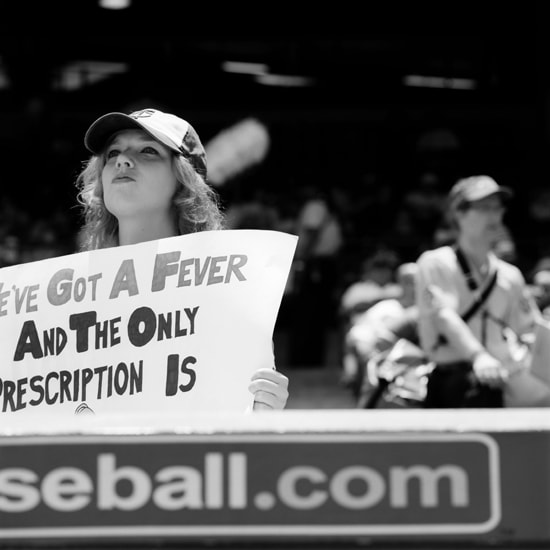

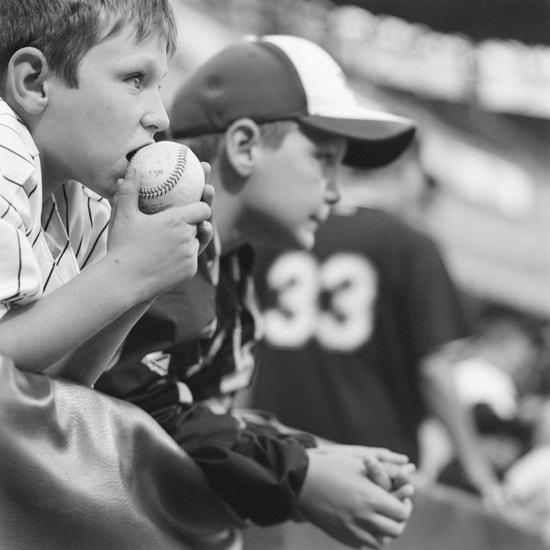

It’s almost time to play ball. The game of catch in front of the dugout will be over soon; the game of catch down the line from the person who, probably more than anyone in this entire ballpark – and I do realize when I say that what it means - a ballpark filled with children, some at their very first game, and with old men who have been to hundreds of games but who have never, ever gotten a ball and who are now of an age where they must pretend that they don’t want one even though they do, oh they do, they’ve been waiting a lifetime for a ball and knowing it is now unlikely to ever happen makes them want it all the more, and the inability to ask for one or even offer much interest in one except perhaps when someone near them in the stands catches one and they say, “Let me see that,” and a person of some or many fewer years hands it over to them, briefly, because an old man’s age here speaks of some expertise though of what exactly it isn’t clear, in that moment an old man can inspect a ball, and hold it, and make known his interest in a ball though even then he has to hold himself back, he can’t sniff it like he wants to or press it to his lips; even an old man such as that, running out of time and knowing it, even he doesn’t want a ball as much as the retarded man does. The retarded man doesn’t disguise his want.

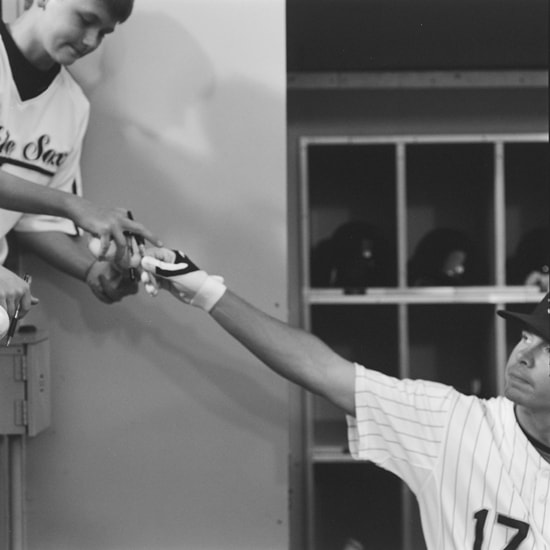

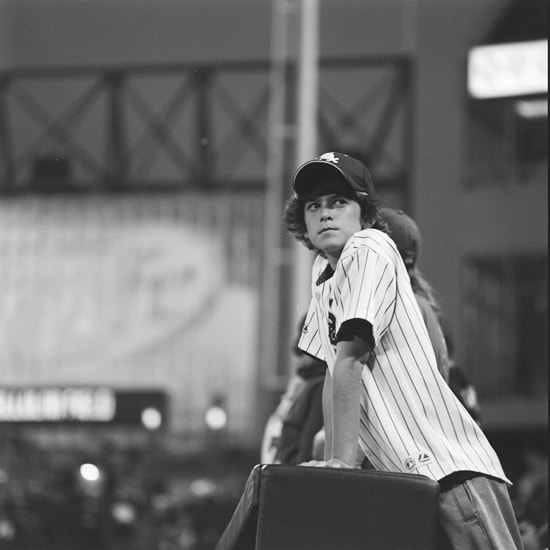

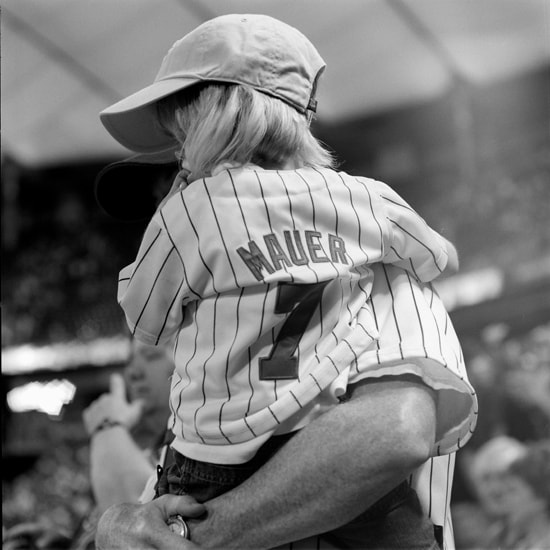

The grounds keeper who never speaks, he says something to one of the guys playing toss, to Cabrera. He says something to him in Spanish and his voice is quiet, conversational, and Cabrera, playing catch, doesn’t look but nods. And when he catches the ball again he turns around and jogs up the line heading straight to the man that people called a boy. He goes straight to him and hands him the ball. And Cabrera doesn’t look around and doesn’t notice or maybe just doesn’t acknowledge the other people, the ones rushing into the aisle and the down the stairs to get close to him. He just hands the ball to the retarded man. And the game is starting, players are running onto the field now, but Cabrera grabs the man, and leans into him, looks right into his eyes and says something I can’t hear.

People cheered. They were cheering for the retarded man, who turned to the crowd and held up his ball and even stomped his feet a little bit because there had to be someplace for all that joy to go and well, his feet were as good a place as any.

I’d like to tell you Cabrera played great that night, that he hit the winning run or saved the day with some dazzling play and well, he actually might have. I heard the crowd call out “O.C.!” from time to time. But to tell you the truth, I don’t really remember the details of game. In fact, I hardly ever remember them.

I was in the camera well next to the visitors’ dugout and there were people in the stands calling to me like they always do, asking for a ball. I try generally in this situation not to look up but someone tapped me on the shoulder, a woman about my age and she said, “It would be nice if we could get that boy a ball.” And she pointed, or rather gestured with her chin, not to a boy but a man, a retarded man. He was about the same age as the woman and me. And he really wanted a ball. He was looking, reaching, calling out even though the time for balls and autographs had passed awhile ago. The game’s about to start.

Others join the woman too, asking if I could get the “kid” a ball. I said, “I wish I could,” and my heart is breaking a little bit because the poor timing of the retarded man’s request makes it seem especially innocent. I frown, look around, maybe pout a little so people know I mean it: “I wish I could.” But I can’t. There are rules against credentialed press – like me – asking for player autographs, but there are unspoken rules too. You don’t speak or interact with them on the field, you don’t even say hello. And you certainly don’t ask for baseballs.

Plus, the game’s about to start. The anthem is over. A couple of infielders are playing catch right in front of the dugout just before the game starts. Any second they’ll turn and take that ball into the dugout with them. They’re all business right now. And the man, despite his shouts, is probably a little too far down the line to be noticed anyway.

The head groundskeeper in Chicago looks like an actor and rarely speaks. Mostly he watches. He watches the field like everyone else watches the game. He also watches clouds.

It’s almost time to play ball. The game of catch in front of the dugout will be over soon; the game of catch down the line from the person who, probably more than anyone in this entire ballpark – and I do realize when I say that what it means - a ballpark filled with children, some at their very first game, and with old men who have been to hundreds of games but who have never, ever gotten a ball and who are now of an age where they must pretend that they don’t want one even though they do, oh they do, they’ve been waiting a lifetime for a ball and knowing it is now unlikely to ever happen makes them want it all the more, and the inability to ask for one or even offer much interest in one except perhaps when someone near them in the stands catches one and they say, “Let me see that,” and a person of some or many fewer years hands it over to them, briefly, because an old man’s age here speaks of some expertise though of what exactly it isn’t clear, in that moment an old man can inspect a ball, and hold it, and make known his interest in a ball though even then he has to hold himself back, he can’t sniff it like he wants to or press it to his lips; even an old man such as that, running out of time and knowing it, even he doesn’t want a ball as much as the retarded man does. The retarded man doesn’t disguise his want.

The grounds keeper who never speaks, he says something to one of the guys playing toss, to Cabrera. He says something to him in Spanish and his voice is quiet, conversational, and Cabrera, playing catch, doesn’t look but nods. And when he catches the ball again he turns around and jogs up the line heading straight to the man that people called a boy. He goes straight to him and hands him the ball. And Cabrera doesn’t look around and doesn’t notice or maybe just doesn’t acknowledge the other people, the ones rushing into the aisle and the down the stairs to get close to him. He just hands the ball to the retarded man. And the game is starting, players are running onto the field now, but Cabrera grabs the man, and leans into him, looks right into his eyes and says something I can’t hear.

People cheered. They were cheering for the retarded man, who turned to the crowd and held up his ball and even stomped his feet a little bit because there had to be someplace for all that joy to go and well, his feet were as good a place as any.

I’d like to tell you Cabrera played great that night, that he hit the winning run or saved the day with some dazzling play and well, he actually might have. I heard the crowd call out “O.C.!” from time to time. But to tell you the truth, I don’t really remember the details of game. In fact, I hardly ever remember them.