No Pepper Games

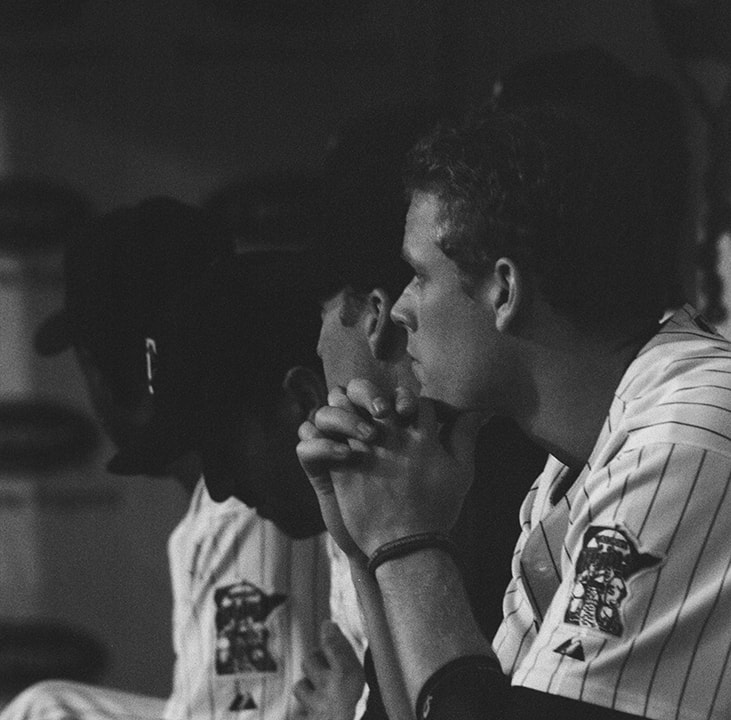

It’s a game of eccentrics. So no one thinks twice when he goes and locks himself in a bathroom stall to tie his shoes. It’s his ritual, that’s it. Who doesn’t have one?

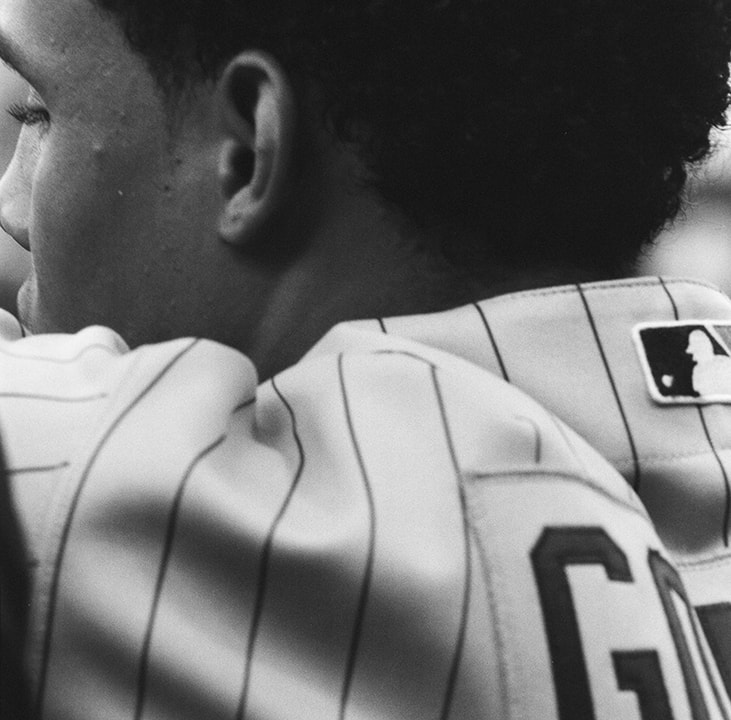

Eight years, six teams not including the minors. Never left a friend behind; never really made one. Mediocre at best but stays employed. Doesn’t ask for much. Gets less than he asks for. It’s his ritual. Who doesn’t have one?

Eight years. Thirty-four years old and feels seventy. Ties his shoes in the bathroom.

Twenty years ago it was so easy. Grew early, moved well. Sixteen years ago it was even easier. Drafted out of high school.

But rookie league was hard. AA was harder. He wasn’t used to anyone being better than he was. He didn’t have the talent, didn’t know how to learn. Didn’t have an edge. So he invented one: Doing as he was told became his secret power.

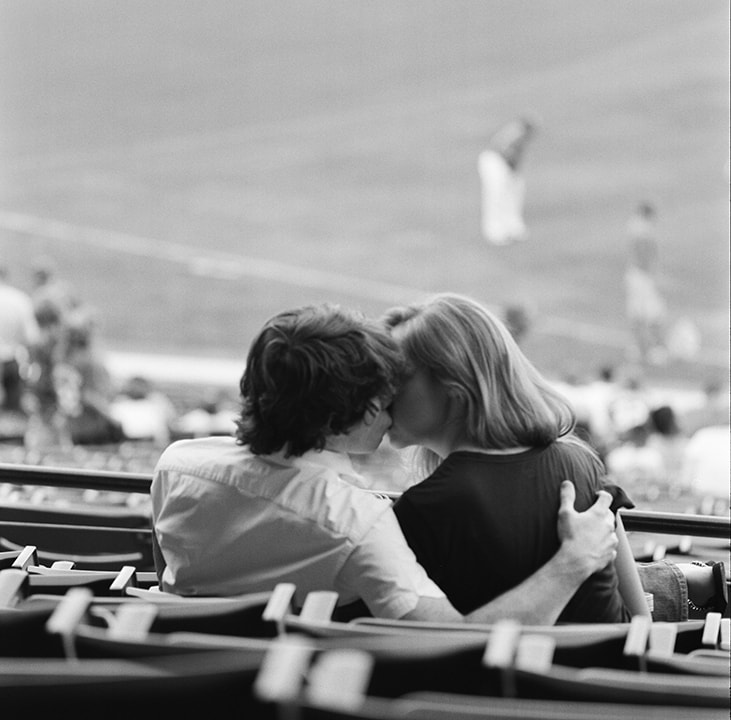

They told him to find a wife, so he did. Pick me, pick me! I’m married and I speak English! That was just about eight years ago.

His wife. Now he’d gladly hand her half his money just so he wouldn’t have to brave that look again. Soon enough, he will. When his playing days are over. Soon enough. Love and career didn’t go as planned. At least he keeps his disappointment to himself.

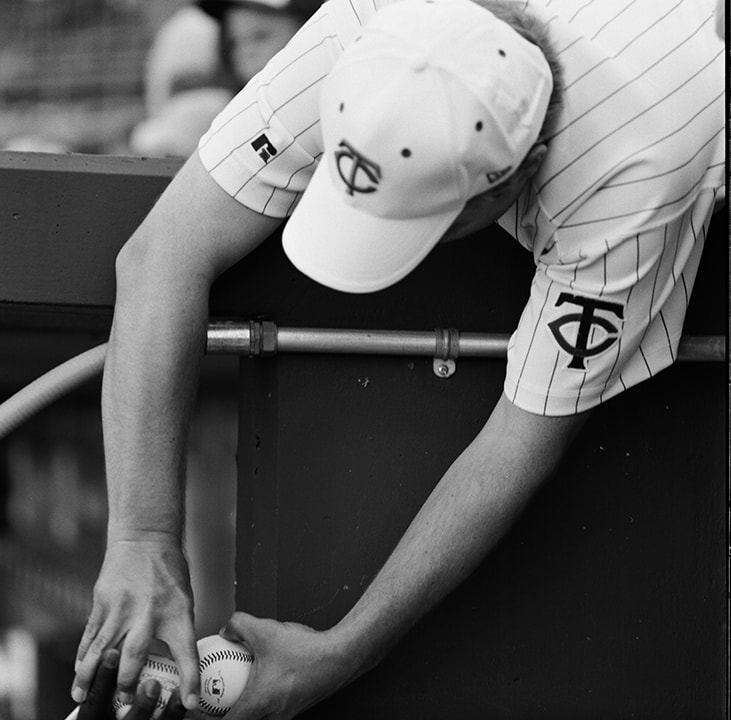

He thinks of all the things he’s never done. He’s never gotten a ring. He’s never walked it off. He’s never been on Sports Center. He’s gone eight years without a post game interview. He’s never really made a friend. He’s never played Pepper.

The old stadiums – the ones he dreamed about when the dream seemed inevitable – the old stadiums had stenciled signs: No Pepper Games. He never knew what it meant, and even when someone told him he was pretty sure they lied. Why have a sign on a major league field telling major league ballplayers not to knock a ball around? But whatever it was, he is who he is. He has a job because he does what he’s told, and doesn’t do what he’s told not to. So: No Pepper Games.

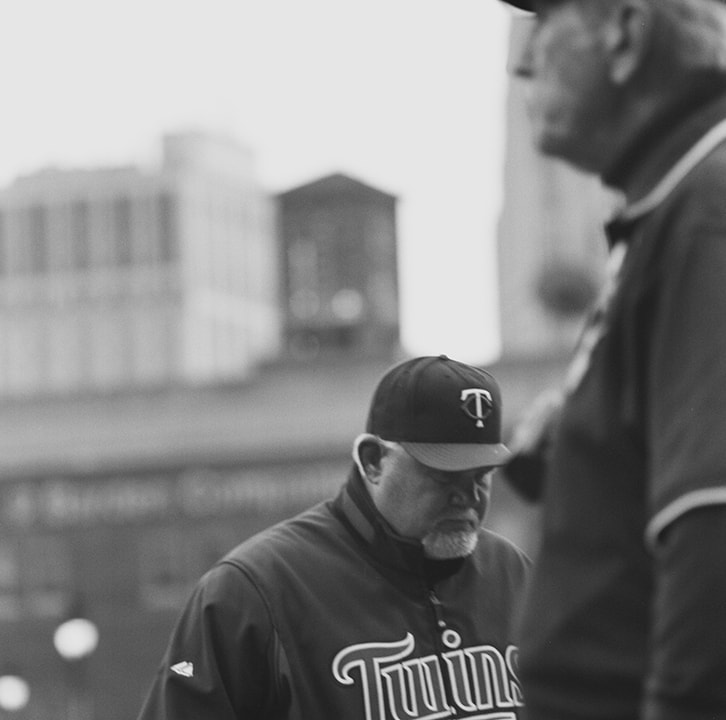

Day game after a night game, and a west coast flight right after: He’s in the starting line-up. He locks himself in the can and ties his shoes. It’s his ritual. Everybody’s got one. Strike it up to superstition but the only streak he’s ever had that he’d want to keep alive is having a job. This job. He’s terrified of losing it. What could possibly come next? Whoring off his flat line stats? Color commentary from a nobody? A coach teaching boys that the game is like loving a woman you love who doesn’t love you back: You watch her sleep around and forgive her. She marries someone else but you still hang around, doing whatever she asks you to, thinking someday she’ll realize you’re the one but she never will. And even though you’ve given her everything and you’re happy just to be her dog and never complain about it, she’ll still throw you away and forget you. Because there’s always another dog, a younger dog, a dog that claims to love her even more than you do.

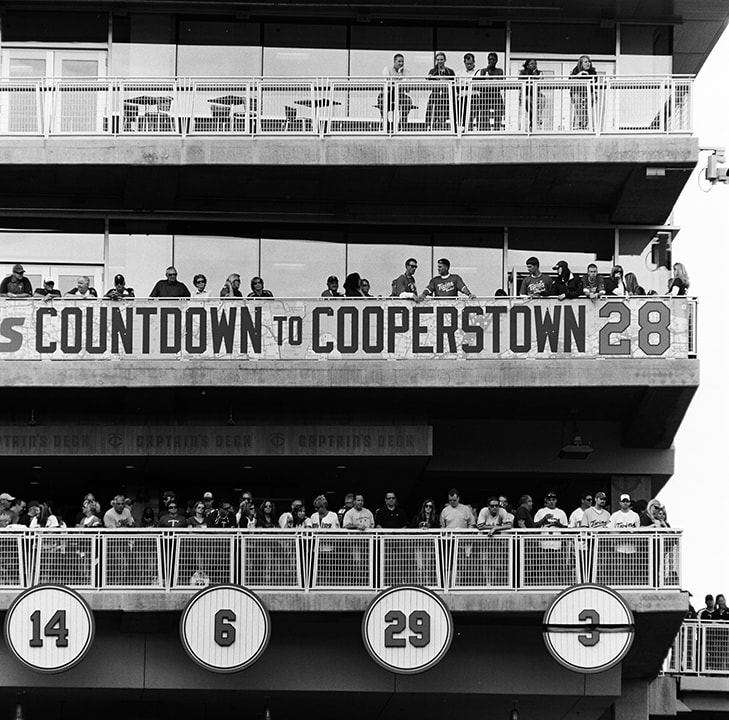

He was never a student of the game. He didn’t care about the history until he realized he would be a part of it. Flat line stats, six teams, hopefully seven or even eight. His name, noted and not mentioned, forever. DiMaggio, Mantle, Aaron, Griffey, Mays. Never saw any of them, but they left marks. Stole numbers. Probably played Pepper too.

So today he’s starting. He locks himself in a stall and ties his shoes. He does this every day, then he tapes down the laces. He doesn’t want anyone to see him wince when his right leg comes up. He flushes the toilet so no one will hear him groan. There’s paper right there to wipe the sweat from his lip and his forehead when he’s done. He wonders how many pregame rituals out there are really just about hiding pain.

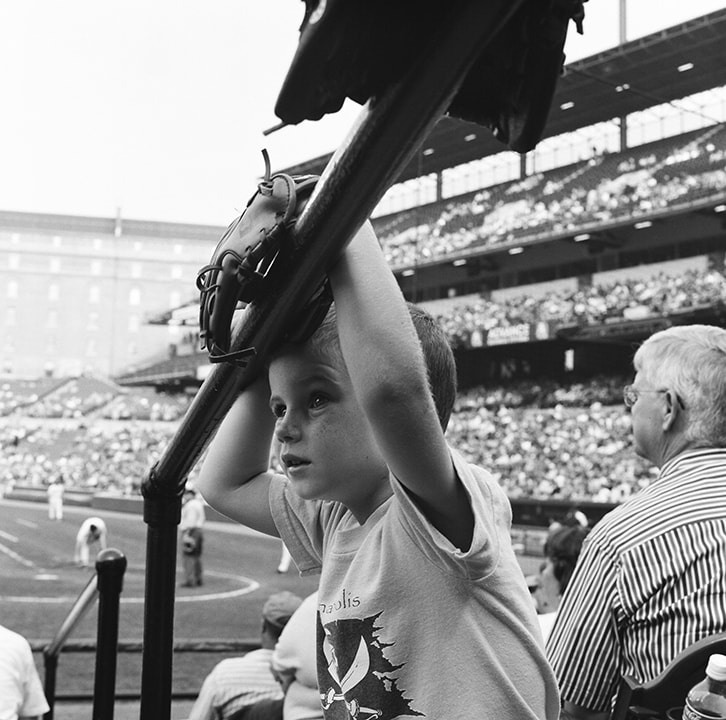

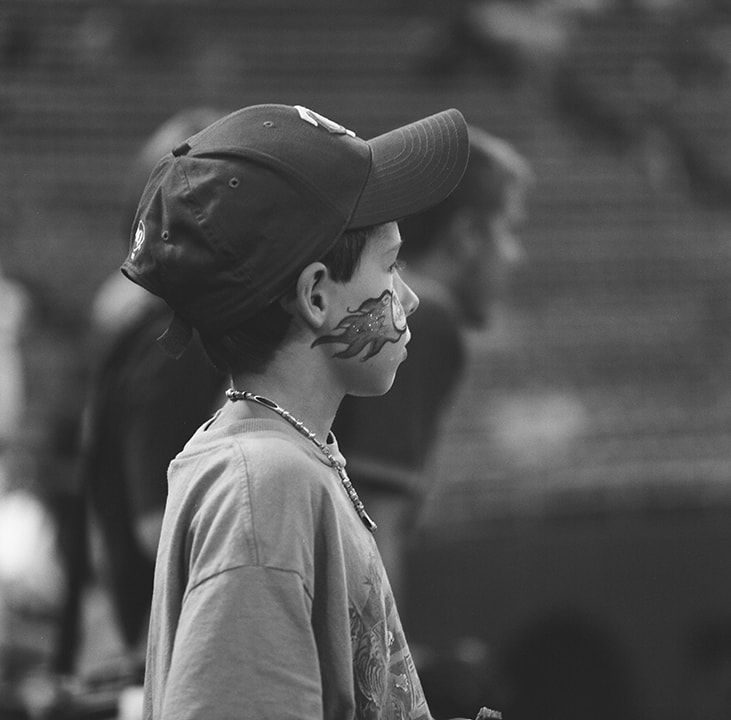

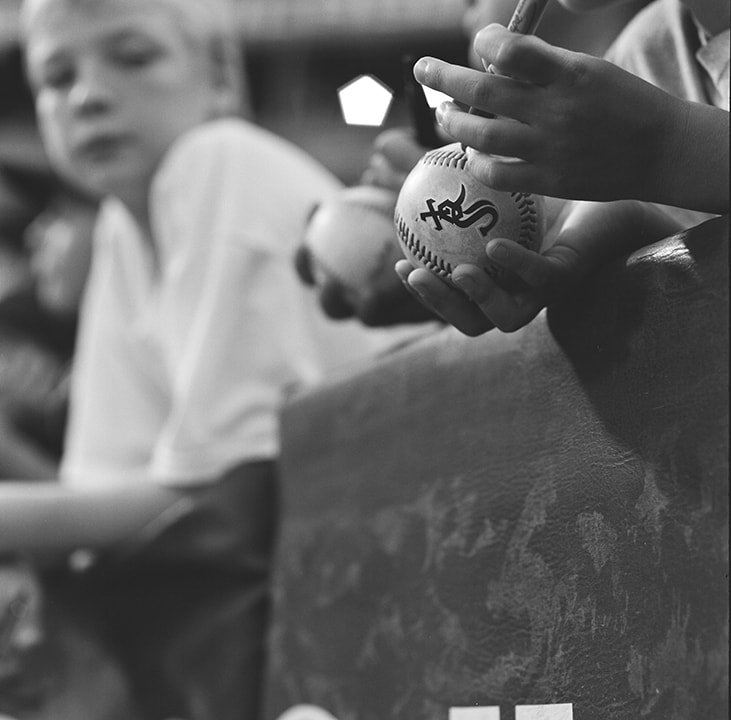

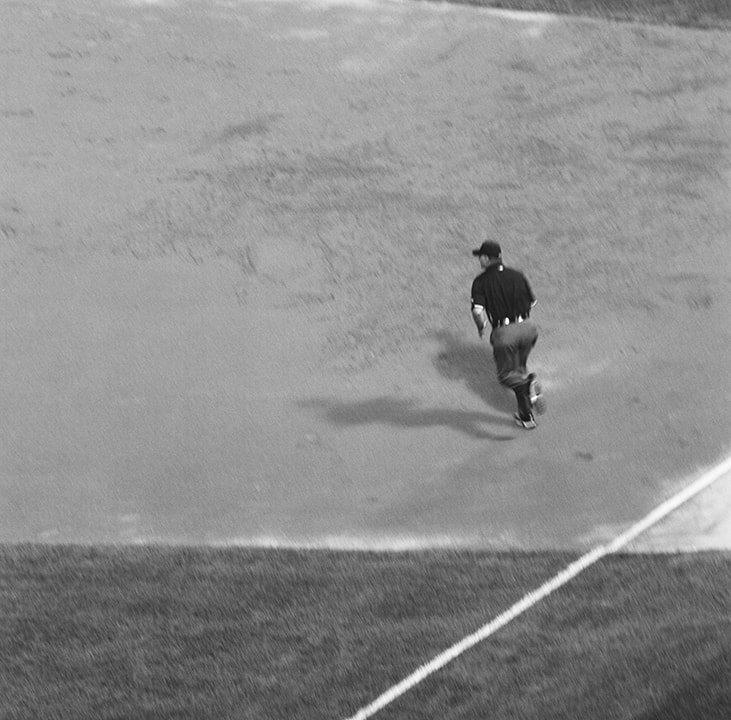

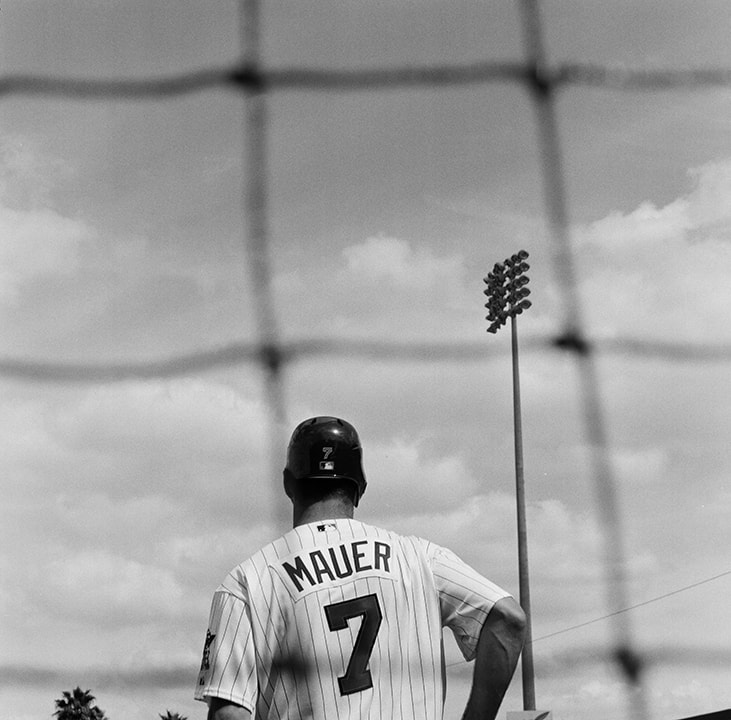

The sun is bright. He steps out of the dugout. He hears a child call his name. His name. Probably read it off the back of his jersey.

He’s never walked it off. He’s never been on Sports Center. He hears a child call his name.

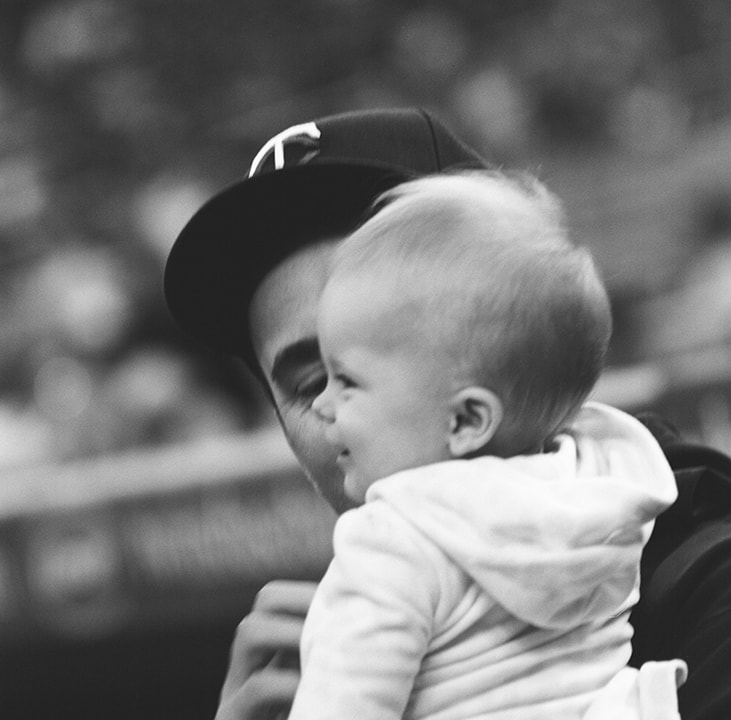

In this moment there are a million things he does not know. He doesn’t know if he’s lucky or cursed. He doesn’t know for sure the tape will hold. He doesn’t know that he will fall in love with a high school Science teacher who worked picking peas, cantaloupe and strawberries when she was just ten years old, and that she will love him back. He doesn’t know she will convince him to get his first dog, and that he will love that dog so much that he will become a bit of an activist. He doesn’t know that he will teach as many girls to play baseball as he will boys, and that he will do so purely for pleasure. He doesn’t know that he will look back on his playing days without a shred of regret, or that his greatest joys lie elsewhere; he doesn’t even know it’s possible that his greatest joys could lie elsewhere. He doesn’t know how to hit a curve. Or a fastball with any movement. Or that, with the game tied in the bottom of the ninth and no one on, his manager will decide, with no outs, not to pinch hit for him, but rather to pinch run for him if he happens to get on. He doesn’t know that he won’t see a single curveball, just a slow fastball without any movement, and that a pinch runner will never come into play.

Eight years, six teams not including the minors. Never left a friend behind; never really made one. Mediocre at best but stays employed. Doesn’t ask for much. Gets less than he asks for. It’s his ritual. Who doesn’t have one?

Eight years. Thirty-four years old and feels seventy. Ties his shoes in the bathroom.

Twenty years ago it was so easy. Grew early, moved well. Sixteen years ago it was even easier. Drafted out of high school.

But rookie league was hard. AA was harder. He wasn’t used to anyone being better than he was. He didn’t have the talent, didn’t know how to learn. Didn’t have an edge. So he invented one: Doing as he was told became his secret power.

They told him to find a wife, so he did. Pick me, pick me! I’m married and I speak English! That was just about eight years ago.

His wife. Now he’d gladly hand her half his money just so he wouldn’t have to brave that look again. Soon enough, he will. When his playing days are over. Soon enough. Love and career didn’t go as planned. At least he keeps his disappointment to himself.

He thinks of all the things he’s never done. He’s never gotten a ring. He’s never walked it off. He’s never been on Sports Center. He’s gone eight years without a post game interview. He’s never really made a friend. He’s never played Pepper.

The old stadiums – the ones he dreamed about when the dream seemed inevitable – the old stadiums had stenciled signs: No Pepper Games. He never knew what it meant, and even when someone told him he was pretty sure they lied. Why have a sign on a major league field telling major league ballplayers not to knock a ball around? But whatever it was, he is who he is. He has a job because he does what he’s told, and doesn’t do what he’s told not to. So: No Pepper Games.

Day game after a night game, and a west coast flight right after: He’s in the starting line-up. He locks himself in the can and ties his shoes. It’s his ritual. Everybody’s got one. Strike it up to superstition but the only streak he’s ever had that he’d want to keep alive is having a job. This job. He’s terrified of losing it. What could possibly come next? Whoring off his flat line stats? Color commentary from a nobody? A coach teaching boys that the game is like loving a woman you love who doesn’t love you back: You watch her sleep around and forgive her. She marries someone else but you still hang around, doing whatever she asks you to, thinking someday she’ll realize you’re the one but she never will. And even though you’ve given her everything and you’re happy just to be her dog and never complain about it, she’ll still throw you away and forget you. Because there’s always another dog, a younger dog, a dog that claims to love her even more than you do.

He was never a student of the game. He didn’t care about the history until he realized he would be a part of it. Flat line stats, six teams, hopefully seven or even eight. His name, noted and not mentioned, forever. DiMaggio, Mantle, Aaron, Griffey, Mays. Never saw any of them, but they left marks. Stole numbers. Probably played Pepper too.

So today he’s starting. He locks himself in a stall and ties his shoes. He does this every day, then he tapes down the laces. He doesn’t want anyone to see him wince when his right leg comes up. He flushes the toilet so no one will hear him groan. There’s paper right there to wipe the sweat from his lip and his forehead when he’s done. He wonders how many pregame rituals out there are really just about hiding pain.

The sun is bright. He steps out of the dugout. He hears a child call his name. His name. Probably read it off the back of his jersey.

He’s never walked it off. He’s never been on Sports Center. He hears a child call his name.

In this moment there are a million things he does not know. He doesn’t know if he’s lucky or cursed. He doesn’t know for sure the tape will hold. He doesn’t know that he will fall in love with a high school Science teacher who worked picking peas, cantaloupe and strawberries when she was just ten years old, and that she will love him back. He doesn’t know she will convince him to get his first dog, and that he will love that dog so much that he will become a bit of an activist. He doesn’t know that he will teach as many girls to play baseball as he will boys, and that he will do so purely for pleasure. He doesn’t know that he will look back on his playing days without a shred of regret, or that his greatest joys lie elsewhere; he doesn’t even know it’s possible that his greatest joys could lie elsewhere. He doesn’t know how to hit a curve. Or a fastball with any movement. Or that, with the game tied in the bottom of the ninth and no one on, his manager will decide, with no outs, not to pinch hit for him, but rather to pinch run for him if he happens to get on. He doesn’t know that he won’t see a single curveball, just a slow fastball without any movement, and that a pinch runner will never come into play.